Monday, December 04, 2006

Haven't entered a new blog for almost a month. Semestral break intervened and I have been in and out of Manila. Haven't returned to blog because I've been reworking the garden in my sister's house. In time for Christmas and the expected avalance of guests.

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

Flora exhibit update

The opening of Flora: Beauty, Desire and Death had two installation works made specifically for it. Jason Dy and Rene Javellana's Contradicting Margaret: Homage to Bro. Kamel, was painted directly on the gallery's wall.

Jay Ticar's work consisting of flowers and fruits embedded in three large blocks of ice lasted for the duration of the opening. As the evening wore off, the block melted leaving a large puddle of water at the center of the Ateneo Art Gallery's main exhibit space. The work was photographed by both still and video camera. A short clip of Ticar's ephemera will be edited for the opening of class on 13 November.

A week later, a potted Camellia thea sinensis arrived from Baguio, courtesy of the Good Shepherd Sisters. The camellia focused attention on the title wall of the exhibit. The red-flowering camellia is no longer in the gallery as it has been sent abroad to become part of a garden of camellias from all over the world, being planted to honor Bro. Kamel in the Checz Republic.

Jay Ticar's work consisting of flowers and fruits embedded in three large blocks of ice lasted for the duration of the opening. As the evening wore off, the block melted leaving a large puddle of water at the center of the Ateneo Art Gallery's main exhibit space. The work was photographed by both still and video camera. A short clip of Ticar's ephemera will be edited for the opening of class on 13 November.

A week later, a potted Camellia thea sinensis arrived from Baguio, courtesy of the Good Shepherd Sisters. The camellia focused attention on the title wall of the exhibit. The red-flowering camellia is no longer in the gallery as it has been sent abroad to become part of a garden of camellias from all over the world, being planted to honor Bro. Kamel in the Checz Republic.

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

Flora opens Wednesday, 11 Oct 2006.

Scheduled for six in the evening, the opening reception for Flora: Beauty, Desire and Death at the Ateneo Art Gallery was delayed because torrential rains hindered the representatives of the museums involved in Zero-in from arriving on time. Metro Manila's main north-south arteries was clogged with traffic. This was aggravated by the dismantling of billboards damaged by Milenyo, the typhoon that breezed through Manila with lightning speed almost two weeks ago. The MMDA said that almot 2000 billboards some as tall as five stories had been knocked down by the typhoon.

After more than a year evolving from a germ of an idea and a hectic two months of borrowing paintings, planning catalogues and wall texts, the opening reception began with a word of welcome by Ramon Lerma, the Director of the Ateneo Art Gallery and a short talk and walkthrough that I gave.

The entrance to the art gallery has been painted a deep green, to evoke a tropical forest Last Thursday, 5 October, Jason Dy a Jesuit scholastic, helped me paint the leaf imprints on one wall of the entrance. The wall frames a brief biography of Georg Josef Kamel. After experimenting on paper how to come up with pleasing shapes, Jason evolved a formula using acrylics as they came out of a tube. I drew some images from Kamel's illustration but as the work was progressing, Jason came up with the idea of showing the life cycle of plants from a seedling to its maturation and to the growth of seeds. I had asked him to paint an arch of leaves. Jason's leaf print work.

The exhibit came up with a total of 62 botanically themed works. The latest was Jay Ticar's installation, where fruits and fruits are deep frozen in ice. Naturally, the four-feet blocks of ice melted as the evening progressed, drenching the red velvet that wrapped the base of the upright blocks. Ticar's work elicited the greatest interest from a group of Fine Arts students who brought out their digital cameras and cellphones to capture this evanescent piece. The gallery has the work on video and will edit a looping piece to show what happened to the ice.

All told the opening was well attended and points to more days of appreciating flora.

After more than a year evolving from a germ of an idea and a hectic two months of borrowing paintings, planning catalogues and wall texts, the opening reception began with a word of welcome by Ramon Lerma, the Director of the Ateneo Art Gallery and a short talk and walkthrough that I gave.

The entrance to the art gallery has been painted a deep green, to evoke a tropical forest Last Thursday, 5 October, Jason Dy a Jesuit scholastic, helped me paint the leaf imprints on one wall of the entrance. The wall frames a brief biography of Georg Josef Kamel. After experimenting on paper how to come up with pleasing shapes, Jason evolved a formula using acrylics as they came out of a tube. I drew some images from Kamel's illustration but as the work was progressing, Jason came up with the idea of showing the life cycle of plants from a seedling to its maturation and to the growth of seeds. I had asked him to paint an arch of leaves. Jason's leaf print work.

The exhibit came up with a total of 62 botanically themed works. The latest was Jay Ticar's installation, where fruits and fruits are deep frozen in ice. Naturally, the four-feet blocks of ice melted as the evening progressed, drenching the red velvet that wrapped the base of the upright blocks. Ticar's work elicited the greatest interest from a group of Fine Arts students who brought out their digital cameras and cellphones to capture this evanescent piece. The gallery has the work on video and will edit a looping piece to show what happened to the ice.

All told the opening was well attended and points to more days of appreciating flora.

Sunday, October 01, 2006

11 October 2006: Opening of Flora: Beauty, Desire and Death

We just experienced a nerve-wracking typhoon that passed through Manila in the record time of 4 hours, between 10 in the morning to 2 in the afternoon of Thursday, 28 September. The typhoon devastated so many trees in the Ateneo de Manila Campus. Fallen are some shade trees and showy flowering trees, including the Talisay (Termenalia cattapa) and the Santol, which appears in George Josef Kamel's illustrations.

But Flora will go on as scheduled. It opens in two weeks time on 11 October 2006. This is Ateneo Art Gallery's participation in Zero-in, whose theme is the convergence of art and science. The typhoon delayed returning the works of artists short-listed in the Ateneo Art Awards as the pick-up needed to transport the works were needed for cleaning up after the typhoon. And there is the concern that rain might damage the works during transport. The high humidity also slows down paint-drying time of the exhibition wall of the Ateneo Art Gallery. But if all goes as scheduled, next week begins the set-up of Flora.

The gallery walls near the entrance will be painted in hunter green, and leaf impresions in various shades of greens, yellows and whites will add texture to the wall. The gallery entrance will give a strong impression of entering a wooded space but not too dense that it feels like a jungle.

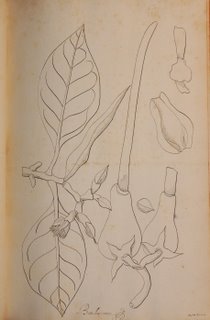

Some works that will be on display are facsimiles of pages from Kamel's illustrations, placed side-by-side with other botanical illustrations from the late-18th and the 19th centuries. More modern renditions of plants will also grace the green walls of the first gallery.

In the main and third gallery, a range of works depicting the floral theme will be displayed. An early work of Arturo Luz, Flower Vendor and a made for opening night installation piece by Jay Ticar will interact with works that are clearly botanical. The works in the galleries will challenge all to reflect on flora and its ineluctable involvement in human life.

The show will unexpectedly be a counterpoint to the decimation of so much plant life in the Ateneo after fierce storm that passed through Manila

But Flora will go on as scheduled. It opens in two weeks time on 11 October 2006. This is Ateneo Art Gallery's participation in Zero-in, whose theme is the convergence of art and science. The typhoon delayed returning the works of artists short-listed in the Ateneo Art Awards as the pick-up needed to transport the works were needed for cleaning up after the typhoon. And there is the concern that rain might damage the works during transport. The high humidity also slows down paint-drying time of the exhibition wall of the Ateneo Art Gallery. But if all goes as scheduled, next week begins the set-up of Flora.

The gallery walls near the entrance will be painted in hunter green, and leaf impresions in various shades of greens, yellows and whites will add texture to the wall. The gallery entrance will give a strong impression of entering a wooded space but not too dense that it feels like a jungle.

Some works that will be on display are facsimiles of pages from Kamel's illustrations, placed side-by-side with other botanical illustrations from the late-18th and the 19th centuries. More modern renditions of plants will also grace the green walls of the first gallery.

In the main and third gallery, a range of works depicting the floral theme will be displayed. An early work of Arturo Luz, Flower Vendor and a made for opening night installation piece by Jay Ticar will interact with works that are clearly botanical. The works in the galleries will challenge all to reflect on flora and its ineluctable involvement in human life.

The show will unexpectedly be a counterpoint to the decimation of so much plant life in the Ateneo after fierce storm that passed through Manila

Sunday, September 17, 2006

Flora coming soon

Flora: Beauty, desire and death is less than a month away. The Ateneo Art Gallery is making preparations for the exhibition. We visited Yasmin Almonte at the University of the Philippines' College of Fine Arts and chose about six of her works from 2004-06 that shows her engagement with the floral theme and women's issue. Joel de Leon and Lisa both agree that her works are powerful and that she should be better known.

Tuesday we make a quick dash to Yasmin's house/studio to make arragements for the paintings we are borrowing. We should also be visiting Chelay Dans, if I can make the appointment with her for Tuesday. We'll also be discussing the catalogue that goes with the exhibition.

Tuesday we make a quick dash to Yasmin's house/studio to make arragements for the paintings we are borrowing. We should also be visiting Chelay Dans, if I can make the appointment with her for Tuesday. We'll also be discussing the catalogue that goes with the exhibition.

Monday, August 28, 2006

Flora and Zero-in

Zero-in— an annual cooperative project among five museums, namely, the Ateneo Art Gallery, Bahay Tsinoy, the Ayala Museum, the Lopez Museum, Museong Pambata—has decided to focus this year's exhibitions on the theme: the convergence of arts and the sciences.

This is the write-up for the Ateneo Art Gallery's Flora: Beauty, Desire and Death.

Flora: Beauty, Desire & Death

Flora: Beauty, Desire and Death, an exhibition commemorating the tercentenary of Bro.Georg Jose Kamel, S.J.’s death, brings in dialogue the arts and sciences by meditating on the role images and illustrations play in the development of these diverse disciplines. While science uses images as a support for texts and equations, art employs images less for their denotative value but for their connotative repercussions. Images in science point to precise facts, images in art open possibilities for exploration.

Plants, what botanist label generically as FLORA, hardly figure as a major subject in Western Art. If they do they are often relegated as secondary decorative or allusive elements in a work whose subject matter is almost always the human.

Still life or what the Italians call natura morta is the closest there is to making flora the subject matter; but still life paintings are often regarded as secondary, no more than exercises done by a schoolboy or by an artist in between more serious works. When flora becomes the subject matter of vanitas or memento mori paintings, plant life is subsumed under the more important pole of the metaphor, life’s transitoriness and the vanity of all things—“Vanitas vanitatis.”

When the modern American artist Georgia O’Keefe painted flowers, blown to gargantuan size, they stunned the art world. O’Keefe illustrated how flora could speak loudly. Flora appears to be more than what it is; no longer mere decoration they are the major premise in the syllogism of metaphors. Likewise, when Judy Chicago did her installation, The Supper, to commemorate women who steered human history, she took to flowers as the central motif for her ceramic plates—flowers alluring for their beauty, flowers clearly erotic.

In the East, flora fares much much better; Chinese schools of painting specialize in depicting plant life. In fact, the first exercises in learning how to handle the Chinese brush are mastering the strokes for the bamboo and the ground orchid.

While the East emphasizes harmony with nature, the West has, especially since the colonial period, had a conquistador mentality toward nature. Lands—foreign lands—had to be occupied, claimed in the name of this or that monarch. And the curious yield of the land—plants and animals—were captured and collected, carefully recorded and reported back to the mother country. When possible specimens of these exotica and curiositias found their way to the European courts and then to the rest of Europe. Thus, did travel the pineapple and the tomato, the corn and the turkey. And the spices, which spurred colonial expansion in the first place.

Colonialism was spurred by desire, an eros to expand, to conquer and own. Whether the motive was noble—to spread civilization and the true faith—or mundane and crass—to fill the coffers of the monarchy or civil state, there was something alluring in the colonized spaces that kindled desire. That desire was fueled by the beauty of the object to be conquered. There was much novel beauty in the lands conquered, impenetrable rain forest, harboring orchids and epiphytes, rain-drenched lands where it was perpetual summer and where cycles of birth and death were abridged as mushrooms and fungi sprouted overnight to wither by night fall.

Beauty was often subsumed under utility. The durability and exoticism of tropical woods with colors ranging from blonde to midnight black, and patinas that gleamed like polish onyx were a sure lure to merchants. Herbs known for their healing properties, for lowering fever, stilling the innards and relieving melancholia. And there were the spices, the oils, the fiber—all fodder for trade. Beauty fanned the embers of acquisitive desire.

Yet the very lands, which the conquistadors set out to conquer and rule, proved to be their own enemy as strange illnesses struck them. As the land proved to be more unyielding and reticent than they expected. The very tropics, which was the hothouse for a variety of species, was also incubator of many unknown diseases, and an unyielding leech that sucked their energies.

So the conquistadors set out to find cures for their aches and pains, to find balm for the tropic heat, and slow down the progress of inevitable death.

Thus, interest in matters botanical, even with Bro. George Josef Kamel, was fueled not only by intellectual curiosity but also, and mainly so, by very practical considerations. How to find remedies and cures in nature’s pharmacopæia of plants, roots, flowers, barks and fruits. It is the desire to stem death, to find a way out that marks the botanical works of early missionary researchers. So many of the specimens drawn by Kamel are marked with Nux. ungt. (nux ungenta), nuts used as unguents, or vom/ vomitrix, purgatives. The medical theory and practice then current prescribed the purgative as a cure-all for many illnesses. If they are not medicinal, the plants drawn by Kamel have practical uses, like hardwoods—molave, narra, balayong and the like—used for building houses more permanent than the bahay kubo.

So desire, beauty and death dance a round in the conquistador’s world. It is this round that the Ateneo de Manila Art Gallery’s exhibition Flora traces in an exhibition to honor a pioneer botanist, Bro. Kamel.

The Exhibition

Flora the Ateneo de Manila’s Art Gallery’s offering for Zero-in dances to the triple theme of beauty, desire and death as this is expressed in the art works in the Ateneo and other collections. Select works in the Ateneo’s collection, augmented by works loaned by two important women artist and a botanical illustrator, dance in a quadrille consisting of four sets: the properly botanical, where the overall theme of the exhibition is sounded and three smaller exhibits where the triple themes are displayed separately.

Interacting with the works of Wilwayco, Soler, Ana Fer, Sancho and others will be reproductions of Kamel’s botanical illustrations, facsimiles of botanical illustrations done in or about the Philippines by the 1795 Juan del Cuellar Expedition and by Fray Manuel Blanco in the 19th century.

Featured will be works by women artists Araceli Dans and Yasmin Almonte. Dans, who recently had a retrospective of her works, is best known for her flower and calado series. Painted with meticulous care, akin to the miniaturismo of the 19th century, Dans captures the evanescent allure of common plants, like the variegated croton or San Francisco. Contrasting the textures and forms of plants with their expression in the fine craft of embroidery, Dans has subtly interwoven a subtext about women and their lives, a subtext not immediately obvious in the complex of metaphors about nature and the human, the natural and the hand-made.

Almonte’s raw image of plants, their flowers and fruits, burst forth as objects of desire and as symbols of human desiring. In contrast to Dans’ carefully executed brush strokes, and minute renderings are Almonte’s gestural lines vibrant with emotion. If Dans appeals visually through fine craftsmanship, Almonte’s appeal is visceral. Almonte's featured pieces are drawn from a body of work done between 2004 and 2006. Beginning with more figurative and colorful figures Almonte's works are metamorphosing toward one which is more abstract and monochromatic as she engages with flora as the prime metaphor of her works. The 2006 pieces have not been publicly shown, this exhibition will be their inaugural

Underneath the alluring veneer of flora lies themes more dark and foreboding; Dans' newer calado hides images of women oppressed and marginalized, the alluring flower is beginning to show signs of decay or is juxtaposed with the detritus of urban life. Flora, then, is a more power-filled metaphor than expected.

The Exhibition’s Honoree

Bro. Josef Georg Kamel was a Jesuit brother who arrived in the Philippines in the 17th century and continued to be active as a pharmacist and naturalist until his death on 2 May 1706. In Europe, Bro. Kamel was known for his botanical research because his catalogue of Philippine plants was published as a supplement (“Herbarium aliarumque stirpitum in insula Luzone Phippiniarum prima noscentium”) to the magnum opus of the British botanist John Ray, Historia Plantarum.

The leading scientific and scholarly circle in Britain, the British Royal Society, sponsored the publication of Ray’s History. At this time, the science of botany was being established on a more solid empirical footing by the careful collection and classification of plants in the discipline that was to evolve as botanical taxonomy. While the taxonomy did not come to full fruition until the binomial system of Karl Linne (Linneaus), who lived a generation after Ray and Kamel, it was the work of these pioneers who amassed information about the biota of the world that was the backbone of Linneaus’ work.

Bro. Kamel was born in Bruno, Moravia on 21 April 1661 in a house near the Židovská (Jew’s) Gate. His father Andreas was a master shearer. At 17, he may have entered the Jesuit mission school in Vienna whence he entered the Jesuit novitiate. On 12 November 1682, he joined the Jesuit province of Bohemia and in 1687, while still in late 20s, he arrived in the Philippines, where in 15 August 1696 he pronounced his final vows. He spent his entire active ministry in Manila at the Colegio de San Ignacio in Intramuros where he was assigned as pharmacist and where he conducted his botanical research and at the hospital of La Misericordia. Eighteenth-century plans of the Colegio indicate that the school had a number of enclosed gardens, even a small orchard. Perhaps, these gardens were planted by Kamel with botanical specimens gathered from all over the Philippines. The Misericordia was a lay organization established to assist the sick and dying and perform other works of mercy. The organization maintained a hospital in Intramuros.

Kamel was in correspondence, it seems, with other Jesuits in the field as his botanical illustrations cite others as the source for the information he had amassed, just as he was in correspondence with still another European botanist and naturalist, James Petiver. Kamel is credited with introducing the igasud (Strychnos ignatii), the source of strychnine, to Europe. Igasud was known as a purgative among the Visayans, and its active ingredient strychnine was poisonous.

Kamel’s sensitive line drawings (or copies of his drawings), preserved in the Jesuit Archives at Louvain, suggest that he illustrated from live specimens rather than from mounted and dried specimens as was common in Europe. Luc Dhaeze, who describes himself as an amateur botanist who has been growing camellias for years, says that the “The manuscript came into the possession of French botanist Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (1748-1836), and was bought by the Belgian count Alfred de Limminghe (Gentinnes) on February 6, 1858 at the sale of the possessions of the former. De Limminghe presented the manuscript as a gift to the Jesuit college in Leuven.”

To honor Bro. Kamel, Linnaeus named the flowering plant Camellia thea sinensis of the tea family, after him. Popularly know as Camellia, the flower reach iconic heights when it became the title of a popular novel, The Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas Fils. The flower is a popular garden plant and has countless hybrids and cultivars.

Kamel is one in a line of botanists who studied the biota of the Philippines. Important as he was, he was no pioneer; other missionaries had already made copious notes about the “natural history” of the Philippines. The Jesuit Francisco Alzina had already written a multivolume work on the natural history of the Visayas, devoting a considerable portion of the first book to plants. Many missionaries were interested in the medicinal characteristic of plants, that could augment the pharmacopæia of potions, ointments, simples and cures that they brought with them from Europe. These missionaries produced books on plantas medicinales.

Almost a century after Kamel’s death the Spanish crown commissioned Juan del Cuellar to conduct a botanical survey of the Philippines in 1795. Del Cuellar employed Filipino artists to illustrate for him. Unfortunately we know nothing about these artists, except that they seem to have illustrated from pressed specimens gathered by the del Cuellar expedition as the artificial arrangement of branches and leaves indicate.

In the 19th century, the Augustinian prior and botanist, Manuel Blanco published Flora de Filipinas, illustrated through a collaborative effort of many Filipino artists. This is the best-known of the locally done botanical books from the colonial period. The published text had full color lithographs and came as a series. Blanco’s Flora enjoyed great popularity and even went into a second printing, although less opulent than the first because the illustrations were no longer in full color. The popularity of Flora de Filipinas may have eclipsed Kamel’s fame because Fray Blanco’s work became the touchstone of botanical knowledge beginning the 19th century.

The Ateneo de Manila Art Gallery’s Zero-in offering Flora: Beauty, Desire and Death joins an international celebration of Kamel’s life and achievement.

As a supplement to Flora, a blogsite (letrasyfiguras.blogspot.com) featuring selected illustrations from Kamel has been created. This site links to the Ateneo de Manila Art Gallery site (gallery.ateneo.edu) where other articles related to Flora are posted.

This is the write-up for the Ateneo Art Gallery's Flora: Beauty, Desire and Death.

Flora: Beauty, Desire & Death

Flora: Beauty, Desire and Death, an exhibition commemorating the tercentenary of Bro.Georg Jose Kamel, S.J.’s death, brings in dialogue the arts and sciences by meditating on the role images and illustrations play in the development of these diverse disciplines. While science uses images as a support for texts and equations, art employs images less for their denotative value but for their connotative repercussions. Images in science point to precise facts, images in art open possibilities for exploration.

Plants, what botanist label generically as FLORA, hardly figure as a major subject in Western Art. If they do they are often relegated as secondary decorative or allusive elements in a work whose subject matter is almost always the human.

Still life or what the Italians call natura morta is the closest there is to making flora the subject matter; but still life paintings are often regarded as secondary, no more than exercises done by a schoolboy or by an artist in between more serious works. When flora becomes the subject matter of vanitas or memento mori paintings, plant life is subsumed under the more important pole of the metaphor, life’s transitoriness and the vanity of all things—“Vanitas vanitatis.”

When the modern American artist Georgia O’Keefe painted flowers, blown to gargantuan size, they stunned the art world. O’Keefe illustrated how flora could speak loudly. Flora appears to be more than what it is; no longer mere decoration they are the major premise in the syllogism of metaphors. Likewise, when Judy Chicago did her installation, The Supper, to commemorate women who steered human history, she took to flowers as the central motif for her ceramic plates—flowers alluring for their beauty, flowers clearly erotic.

In the East, flora fares much much better; Chinese schools of painting specialize in depicting plant life. In fact, the first exercises in learning how to handle the Chinese brush are mastering the strokes for the bamboo and the ground orchid.

While the East emphasizes harmony with nature, the West has, especially since the colonial period, had a conquistador mentality toward nature. Lands—foreign lands—had to be occupied, claimed in the name of this or that monarch. And the curious yield of the land—plants and animals—were captured and collected, carefully recorded and reported back to the mother country. When possible specimens of these exotica and curiositias found their way to the European courts and then to the rest of Europe. Thus, did travel the pineapple and the tomato, the corn and the turkey. And the spices, which spurred colonial expansion in the first place.

Colonialism was spurred by desire, an eros to expand, to conquer and own. Whether the motive was noble—to spread civilization and the true faith—or mundane and crass—to fill the coffers of the monarchy or civil state, there was something alluring in the colonized spaces that kindled desire. That desire was fueled by the beauty of the object to be conquered. There was much novel beauty in the lands conquered, impenetrable rain forest, harboring orchids and epiphytes, rain-drenched lands where it was perpetual summer and where cycles of birth and death were abridged as mushrooms and fungi sprouted overnight to wither by night fall.

Beauty was often subsumed under utility. The durability and exoticism of tropical woods with colors ranging from blonde to midnight black, and patinas that gleamed like polish onyx were a sure lure to merchants. Herbs known for their healing properties, for lowering fever, stilling the innards and relieving melancholia. And there were the spices, the oils, the fiber—all fodder for trade. Beauty fanned the embers of acquisitive desire.

Yet the very lands, which the conquistadors set out to conquer and rule, proved to be their own enemy as strange illnesses struck them. As the land proved to be more unyielding and reticent than they expected. The very tropics, which was the hothouse for a variety of species, was also incubator of many unknown diseases, and an unyielding leech that sucked their energies.

So the conquistadors set out to find cures for their aches and pains, to find balm for the tropic heat, and slow down the progress of inevitable death.

Thus, interest in matters botanical, even with Bro. George Josef Kamel, was fueled not only by intellectual curiosity but also, and mainly so, by very practical considerations. How to find remedies and cures in nature’s pharmacopæia of plants, roots, flowers, barks and fruits. It is the desire to stem death, to find a way out that marks the botanical works of early missionary researchers. So many of the specimens drawn by Kamel are marked with Nux. ungt. (nux ungenta), nuts used as unguents, or vom/ vomitrix, purgatives. The medical theory and practice then current prescribed the purgative as a cure-all for many illnesses. If they are not medicinal, the plants drawn by Kamel have practical uses, like hardwoods—molave, narra, balayong and the like—used for building houses more permanent than the bahay kubo.

So desire, beauty and death dance a round in the conquistador’s world. It is this round that the Ateneo de Manila Art Gallery’s exhibition Flora traces in an exhibition to honor a pioneer botanist, Bro. Kamel.

The Exhibition

Flora the Ateneo de Manila’s Art Gallery’s offering for Zero-in dances to the triple theme of beauty, desire and death as this is expressed in the art works in the Ateneo and other collections. Select works in the Ateneo’s collection, augmented by works loaned by two important women artist and a botanical illustrator, dance in a quadrille consisting of four sets: the properly botanical, where the overall theme of the exhibition is sounded and three smaller exhibits where the triple themes are displayed separately.

Interacting with the works of Wilwayco, Soler, Ana Fer, Sancho and others will be reproductions of Kamel’s botanical illustrations, facsimiles of botanical illustrations done in or about the Philippines by the 1795 Juan del Cuellar Expedition and by Fray Manuel Blanco in the 19th century.

Featured will be works by women artists Araceli Dans and Yasmin Almonte. Dans, who recently had a retrospective of her works, is best known for her flower and calado series. Painted with meticulous care, akin to the miniaturismo of the 19th century, Dans captures the evanescent allure of common plants, like the variegated croton or San Francisco. Contrasting the textures and forms of plants with their expression in the fine craft of embroidery, Dans has subtly interwoven a subtext about women and their lives, a subtext not immediately obvious in the complex of metaphors about nature and the human, the natural and the hand-made.

Almonte’s raw image of plants, their flowers and fruits, burst forth as objects of desire and as symbols of human desiring. In contrast to Dans’ carefully executed brush strokes, and minute renderings are Almonte’s gestural lines vibrant with emotion. If Dans appeals visually through fine craftsmanship, Almonte’s appeal is visceral. Almonte's featured pieces are drawn from a body of work done between 2004 and 2006. Beginning with more figurative and colorful figures Almonte's works are metamorphosing toward one which is more abstract and monochromatic as she engages with flora as the prime metaphor of her works. The 2006 pieces have not been publicly shown, this exhibition will be their inaugural

Underneath the alluring veneer of flora lies themes more dark and foreboding; Dans' newer calado hides images of women oppressed and marginalized, the alluring flower is beginning to show signs of decay or is juxtaposed with the detritus of urban life. Flora, then, is a more power-filled metaphor than expected.

The Exhibition’s Honoree

Bro. Josef Georg Kamel was a Jesuit brother who arrived in the Philippines in the 17th century and continued to be active as a pharmacist and naturalist until his death on 2 May 1706. In Europe, Bro. Kamel was known for his botanical research because his catalogue of Philippine plants was published as a supplement (“Herbarium aliarumque stirpitum in insula Luzone Phippiniarum prima noscentium”) to the magnum opus of the British botanist John Ray, Historia Plantarum.

The leading scientific and scholarly circle in Britain, the British Royal Society, sponsored the publication of Ray’s History. At this time, the science of botany was being established on a more solid empirical footing by the careful collection and classification of plants in the discipline that was to evolve as botanical taxonomy. While the taxonomy did not come to full fruition until the binomial system of Karl Linne (Linneaus), who lived a generation after Ray and Kamel, it was the work of these pioneers who amassed information about the biota of the world that was the backbone of Linneaus’ work.

Bro. Kamel was born in Bruno, Moravia on 21 April 1661 in a house near the Židovská (Jew’s) Gate. His father Andreas was a master shearer. At 17, he may have entered the Jesuit mission school in Vienna whence he entered the Jesuit novitiate. On 12 November 1682, he joined the Jesuit province of Bohemia and in 1687, while still in late 20s, he arrived in the Philippines, where in 15 August 1696 he pronounced his final vows. He spent his entire active ministry in Manila at the Colegio de San Ignacio in Intramuros where he was assigned as pharmacist and where he conducted his botanical research and at the hospital of La Misericordia. Eighteenth-century plans of the Colegio indicate that the school had a number of enclosed gardens, even a small orchard. Perhaps, these gardens were planted by Kamel with botanical specimens gathered from all over the Philippines. The Misericordia was a lay organization established to assist the sick and dying and perform other works of mercy. The organization maintained a hospital in Intramuros.

Kamel was in correspondence, it seems, with other Jesuits in the field as his botanical illustrations cite others as the source for the information he had amassed, just as he was in correspondence with still another European botanist and naturalist, James Petiver. Kamel is credited with introducing the igasud (Strychnos ignatii), the source of strychnine, to Europe. Igasud was known as a purgative among the Visayans, and its active ingredient strychnine was poisonous.

Kamel’s sensitive line drawings (or copies of his drawings), preserved in the Jesuit Archives at Louvain, suggest that he illustrated from live specimens rather than from mounted and dried specimens as was common in Europe. Luc Dhaeze, who describes himself as an amateur botanist who has been growing camellias for years, says that the “The manuscript came into the possession of French botanist Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (1748-1836), and was bought by the Belgian count Alfred de Limminghe (Gentinnes) on February 6, 1858 at the sale of the possessions of the former. De Limminghe presented the manuscript as a gift to the Jesuit college in Leuven.”

To honor Bro. Kamel, Linnaeus named the flowering plant Camellia thea sinensis of the tea family, after him. Popularly know as Camellia, the flower reach iconic heights when it became the title of a popular novel, The Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas Fils. The flower is a popular garden plant and has countless hybrids and cultivars.

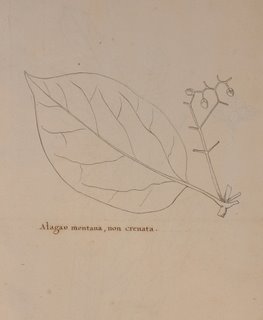

Kamel is one in a line of botanists who studied the biota of the Philippines. Important as he was, he was no pioneer; other missionaries had already made copious notes about the “natural history” of the Philippines. The Jesuit Francisco Alzina had already written a multivolume work on the natural history of the Visayas, devoting a considerable portion of the first book to plants. Many missionaries were interested in the medicinal characteristic of plants, that could augment the pharmacopæia of potions, ointments, simples and cures that they brought with them from Europe. These missionaries produced books on plantas medicinales.

Almost a century after Kamel’s death the Spanish crown commissioned Juan del Cuellar to conduct a botanical survey of the Philippines in 1795. Del Cuellar employed Filipino artists to illustrate for him. Unfortunately we know nothing about these artists, except that they seem to have illustrated from pressed specimens gathered by the del Cuellar expedition as the artificial arrangement of branches and leaves indicate.

In the 19th century, the Augustinian prior and botanist, Manuel Blanco published Flora de Filipinas, illustrated through a collaborative effort of many Filipino artists. This is the best-known of the locally done botanical books from the colonial period. The published text had full color lithographs and came as a series. Blanco’s Flora enjoyed great popularity and even went into a second printing, although less opulent than the first because the illustrations were no longer in full color. The popularity of Flora de Filipinas may have eclipsed Kamel’s fame because Fray Blanco’s work became the touchstone of botanical knowledge beginning the 19th century.

The Ateneo de Manila Art Gallery’s Zero-in offering Flora: Beauty, Desire and Death joins an international celebration of Kamel’s life and achievement.

As a supplement to Flora, a blogsite (letrasyfiguras.blogspot.com) featuring selected illustrations from Kamel has been created. This site links to the Ateneo de Manila Art Gallery site (gallery.ateneo.edu) where other articles related to Flora are posted.

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Opening of Flora Exhibit in honor of Bro. Kamel 10 October 2006

The art exhibit Flora: Beauty, Desire and Death is scheduled to open on 10 October 2006 at the Ateneo Art Gallery. It joins Zero-In, a joint annual program of five museums/ galleries, namely, the Ateneo Art Gallery, the Ayala Museum, the Lopez Museum, the Museong Pambata, and the latest Bahay Tsinoy. This year Zero-In chose as a theme the convergence of Art and Science. Ayala's exhaibition entitled Black Bouquet, will be on the prints of Juvenal Sanso. Museong Pambata features the pressed flower works of Penny Velasco. Bahay Tsinoy will feature Chinese herbal medicine and the Lopez Museum's "Fuzzy Logic" will focus on the impact of new media on the visual arts.

A joint catalogue for Zero-in is being prepared. I wrote a 2000-word essay for Flora, which includes a short boxed article on George Josef Kamel. This week we went through the Ateneo Art Gallery's collection and chose some 30 works related to the theme of Flora. Painter and watercolorist Araceli Limcaoco-Dans invited me to her studio and negotiations to borrow some of her works have been firmed. Its a matter of deciding which of her works will be exhibited. Yasmine Almonte and Geraldine Javier are next in line.

We have discussed the look of the show, probably painting a whole wall of the gallery Hunter Green. I have chosen the identifying icon of the exhibit, which will be a colorized version of the Thea sinensis found in Kamel (See illustration on this blog).

Flora will run until 2007 to coincide with the Linneaus celebrations. Flora promises to be an exciting exhibition on a much neglected theme.

Thursday, August 10, 2006

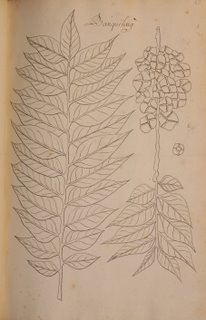

george josef kamel, s.j. drawing of bakiling

It's been a while since I blogged. My laptop went through a lifestyle check, now its functioning smoothly as ever. Also been busy with lots of things, including finishing assemblages for a group show in late October or early November. But am here again with the addition of a new blog.

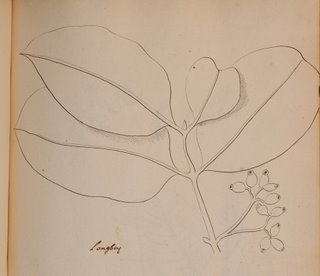

Bankiling [Cicca acida (L.) Merr, Syn. Phyllantus acidus (L.) Skeels, Syn, kagindi, poras (Visayan), Karmay (Tagalog), Malay gooseberry (English)

I’ve always associated this very sour fruit with visits to my mother’s hometown, Capiz. There every summer we would gather bankiling fruits from the huge tree that grew in an aunt’s garden. Occasionally, the fruit would be sold in the local market, but more often than not it was the tree growing in an aunt’s back garden that was the object of childhood avarice. The fruit is so acidic that a childhood dare was to chew a mouthful of this six to eight-lobed drupe and make the craziest grimace or else to masticate the fruit stoically without showing any reaction. The pale yellow fruit grew in bunches just as Kamel draws it.

The tree is small growing between three and ten meters. It has small light green or reddish flowers. I have not seen bangkiling in the markets of Manila or Luzon, its more associated in my memory with the Visayas. Because it is acidic it is not a very popular fruit and may perhaps be going extinct for lack of cultivation. Not a pleasing fruit, nonetheless it is the stuff of memories.

Thursday, July 27, 2006

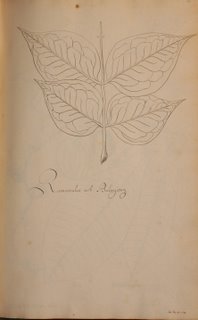

george josef kamel, s.j. drawing of balete

Balete is the generic name for a number of species belonging to the Ficus genus. Ficus benjamina is the common balete trained as bonsai, trimmed to shape and used as landscape material. It is known in English as the strangling or straggling fig or in Visayan dalakit because of the plants ability to attach itself to various surfaces like old masonry and tree bark, which it then envelops in a maze of roots. This slowly destroys masonry and kills the host tree.

F. elastica is a huge tree, characterized by massive aerial roots. This is the banyan, mistakenly referred to as rubber tree or Indian rubber tree because it produces a sticky latex. F. elastica has large, leathery, shiny and veined leaves. Its terminal stipules are reddish. Able to survive in shade, saplings of F. elastica are used for decoration.

Sometimes called ivy F. pumila is a creeping variety of fig. It is a shrub that clings to walls because its short roots produce a stick substance. It is used to cover perimeter walls and concrete buildings. Left alone F. pumila can cover a building to the height of about four stories. When F. pumila matures it produces a large pear shaped fruit near the top. F. lyrata has fiddle shaped leaves, hence the English name fiddle-leaf fig and the Bahasa Indonesia cantik biola (beautiful violin). Ficus are distinguished by leaf shape or form. F. pseudopalma in Tagalog niyog-niyog looks like a palm tree. F. rotundifolia has roundish leaves, while F. triangularis has rounded triangular leaves. F. ulmifolia, locally known as isis, as the species name suggests has elm-like leaves. This plant’s rough surface and tough texture makes it suitable for polishing wood.

Ficus hardiness recommends it as an ornamental, hence, many cultivars have been developed including variegated types.

Ficus is also the stuff of legend. Perhaps the many aerial roots and the dark recesses they produce which characterize some species have suggested that these are dwelling spaces of unseen entities. Folk legend has it that dwendes live in large F. benjamina trees, and that the dark-skinned, tobacco-smoking giant, the kapre, uses it as a lounging chair. Historically, the ficus figures in the story of the Buddha. It was while meditating under the bodhi or peepul tree (F. religiosa L.) that prince Siddharta or Sakyamuni attained enlightenment and became the Buddha. F. religiosa has ovate or heart-shaped leaves terminating in a tapered tail-like tip. Because of its religious connections, F. religiosa figures in Asian folk craft, either as subject-matter of painting or design or as skeletonized leaves on which are painted folk scenes or religious stories.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

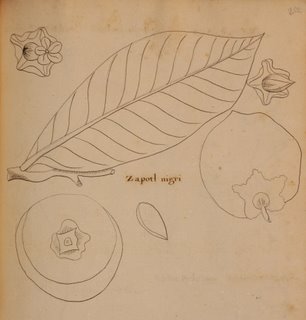

george josef kamel, s.j. drawing of zapote

Zapote. The town of Zapote in Cavite Province is named after a tree introduced from Mexico during colonial times. There are two varieties of zapote or sapote: sapote-negro [Diospyros ebenaster Retz. (black zapote)] and sapote [Pouteria sapota (See Madulid, p. 171 and p. 323)]. As the genus names indicate the two trees are not related. Sapote-negro is related to the persimmon in the family Ebenaceae.

While the two varieties of sapote are planted as ornamentals and as shade tree, the fruit is not very popular in the Philippines. Many have heard of the fruit and know that it is edible but since it is not readily available in the market, hardly anyone I know has seen the fruit much less eaten it. Except for Doc Madulid of the National Museum, whose book A pictorial cyclopedia of Philippine ornamental plants shows a shiny yellow green fruit of the sapote hanging from a branch with leathery, shiny leaves.

Sunday, July 16, 2006

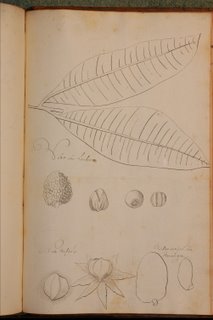

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of pili

Pili [Canarium ovatum Engl. Syn. Canarium pachyphyllum Perkins, Canarium melioides Elmer] Pili is associated with the Bicol region, where the nut is roasted or boiled and used in various sweet culinary preparations like mazapan (marzipan) de pili, pili nut brittle, pastilles and so forth. The oily nut’s mild flavor similar to almond blends well with ice cream and other baked goods. It goes well too roasted and salted.

While the nut is well-known through out the Philippines because it is a favorite pasalubong from Bicol, the violet fruit is hardly known except in Bicol, where it is first blanched or boiled briefly. Then, the fruit is dipped in patis (fish sauce) and eaten skin and pulp, until the hard seed is all that remains.

Pili is endemic to the Philippines where it grows wild in low and medium elevation primary forests in Southern Luzon, parts of the Visayas and Mindanao. While pili is an important crop it is not grown commercially in orchards as most nuts come from the wild.

The tree is a handsome evergreen rising to up to 20 meters. It is highly resistant to wind as its trunk is generally free of branches and branching limited to the upper part of the trunk. Pili lumber is resinous.

Saturday, July 15, 2006

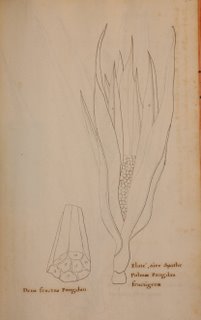

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of pandan flower and fruit

Pandan [Pandanus tectoris] The pandanus or pandan illustrated by Kamel is most likely Pandanus tectoris. There are many pandan species, about 800 trees and shrubs, belonging to the screw pine family like Pandanus odorus, P. latifolius, P. utilissimus, P. odorantissimus and Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. The last cited species is a small shrub whose leaves are used as a mild spice to flavor water, rice and other dishes. A refreshing tea can also be made from P. amaryllifolius leaves.

P. amaryllifolius is largely cultivated and an extensive wild population is unknown.

While P. amaryllifolius is associated with cuisine, Pandanus tectorius or screwpine is a useful tree since its leaves are used for weaving mats, baskets, hats, fans and, in the past, sails for the outrigger boats like the barangay and paraw.

The multi-branched tree grows well to a height of about 8 meters on sandy or rocky shores, where it serves as a windbreak. The tree has aerial roots. Leaves are M-shaped in cross section and notorious for the fine thorns that line its margins and midrib. Flowers are dimorphic: white male flowers have large white bracts while females appear in a head. Both appear at branch tips. The flowers develop into a globular shape, with separate pieces or phalanges that mature to form a deep green color to a orange brown fruit. Kamel illustrates the pandan flower cluster and a portion of the fruit.

Uses: While the fruit has an edible core beneath the fibrous husk, it is hardly eaten in the Philippines and left to mature and fall, whence it becomes animal fodder. Pandan, however, is cultivated because its leaves are used for weaving and may even be found in inshore areas as ornamentals or as barriers because of its thorny leaf. Cultivars of the pandan are available commercially as landscaping material. The dwarf and the varigated varieties are popular.

Friday, July 14, 2006

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of lychee

Lechias. Fresh lychee [Litchi chinensis Sonn.], native to the provinces of Quanzhou and Fujian in southern China, was a harbinger of Christmas. Eagerly awaited like the mandarin oranges and the sweet chestnut, all from China, the appearance of this trio in the Philippine market in late November or early December bode that Christmas was coming. Canning, however, has made the fruit available year round and the successful cultivation of a cultivar developed in Thailand has allowed the tree to flourish in the tropical surroundings of Bulacan rather than the temperate climes to which lychee is endemic. Canned lychee is available year round while the fresh fruit is available even beyond the Christmas season.

Lechias. Fresh lychee [Litchi chinensis Sonn.], native to the provinces of Quanzhou and Fujian in southern China, was a harbinger of Christmas. Eagerly awaited like the mandarin oranges and the sweet chestnut, all from China, the appearance of this trio in the Philippine market in late November or early December bode that Christmas was coming. Canning, however, has made the fruit available year round and the successful cultivation of a cultivar developed in Thailand has allowed the tree to flourish in the tropical surroundings of Bulacan rather than the temperate climes to which lychee is endemic. Canned lychee is available year round while the fresh fruit is available even beyond the Christmas season.The tree is dimorphic, with fruiting females and non-fruiting males. The males, however, are needed to pollinate the female flowers. Lychee is pure delight. Eaten ripe it has a sweet white pulp surrounding a hard brown pith. It can be mixed with other fruits, used as a glaze or used for baked goods. Its distant cousin Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum), introduced from Indonesia in the 1950s grows well in the Philippines.

The inclusion of lychee in Kamel's compendium raises the question whether he found the tree growing and fruiting in the Philippines or whether he drew the fruit and leaf from lychee fruit being sold in the Manila market. If Kamel drew from a living specimen, then lychee was introduced much earlier to the Philippines than is generally supposed.

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

Sunday, July 09, 2006

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of palm leaves

Kamel illustrates details of four species of plant, which he identifies as palms (from top left to bottom right): pandanus, buri, coconut and areca or bunga used for the chew called nga-nga in Tagalog, ma-ma or mamun in Visayan.

Kamel illustrates details of four species of plant, which he identifies as palms (from top left to bottom right): pandanus, buri, coconut and areca or bunga used for the chew called nga-nga in Tagalog, ma-ma or mamun in Visayan. While its leaves are palm-like, Pandanus odorantissimus, the species Kamel illustrates elsewhere, belongs to the Pandanaceæ family. Buri (Corphyra elata Roxb.), coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) and bunga (Areca catechu L.) belong to the Palmæ/ Arecæ family. Of all plants, palms are the most iconic of the tropics. They are also economically useful plants. Pandanus leaves are used for weaving mats, baskets and containers; buri leaves are used likewise. Buri is a favorite material for wide-brimmed sun hats and an alternate to nipa for roof thatching. Coconut's usefulness is endless. It leaves can be woven to make temporary roofs, containers and ornaments. The mid-rib of the compound leaf is stripped and bundled together to make a broom. Its trunk is a sturdy lumber used for temporary post of bridges because it is impervious to water. The list is endless. Areca bound people together because the act of chewing nga-nga was used as a way of showing goodwill; this traditional practice is fast disappearing among urbanites but persists among cultural communities.

Friday, July 07, 2006

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of nipa

Nipa [Nipa fruticans or Nypa fruticans]

“Bahay kubo, kahit munti.” The cube-shaped ubiquitous bahay or balay was a staple of countryside scenery. Today, the balay is disappearing replaced by reinforced concrete, glass and galvanized iron sheet houses in pseudo-Mediterranean or neo-Spanish colonial style, the fruit of hard-earned cash by overseas Filipino workers. But these results of “katas ng Saudi” or Japan, Kuwait, or wherever Filipinos are (and that’s everywhere on the planet) has not erased the mythic aura of the simple and small one-room bahay. It is still part of the national imaginary, resurrected whenever there is need to look Filipino and rural.

This bahay, this dwelling, is truly the fruit of the land, as it is built completely of vegetable matter: bamboo, vines, coconut trunks, timber and—nipa. (Of course, there are those to take short cuts by replacing bamboo dowels with nails, but that’s not how the traditional bahay was built).

Nipa or sasa is known as attap palm, mangrove palm or nipah in the Malaysian Peninsula. Attap in Melayu simply means roof. Nipa grows near the shore often in association with mangrove. Its habitat are the tidal swamps surrounding islands and the banks of waterways leading to the sea. Nipa grows best where tidal and river currents are slow and where there is a generous layer of soft black nutrient rich mud. Part of the plant is submarine, as its roots and short trunk are submerged under water. What rises above the water are the leaves and the flower stalks.

Kamel presents a set of drawings of the nipa, capturing quite accurately the globular inflorescence of the female flowers and the catkin-like male flowers below.

The leaves can grow as high as 9 meters and the flowers mature into a globular cluster of seeds about 25 cm across. As seeds ripen they fall one by one and are dispersed by the tide.

Architectural use: The compound leaf of the nipa produces broad but elongated leaflets. These are separated then folded over a bamboo stick and sewn together with rattan, vine or the outer sheath of the bamboo, drawn thin and fine like a cord. These shingles about a meter in length (width depends on the nipa leaf used) are laid on top of each other for roofing. The distance between shingles depends how thick (therefore how waterproof and long-lasting) the roof is meant to be. Closely shingled roofs with each shingle about an inch apart can last a decade, unless damaged by a strong typhoon or by fire.

In Capiz province, a folk unit used for measuring distances of shingles is the matchbox (approximately 1.25 in x 2.00 in). Closely shingled roofs are distant for the space of isa ka posporo nga nagahigda, that is, a matchbox laid horizontally, while the more distant measure is posporo nga nagatindog, that is, a matchbox laid vertically.

Culinary note: The nipa inflorescence like the coconut’s is tapped before blossoming and yields a sweet sap that is fermented to make tuba sa nipa, an alcoholic drink. In Quezon province, the tuba is processed by distillation to make the potent lambanog (pure alcohol 80 to 90 proof). This is lambanog sa sasa, commonly found in Infanta and Polilio Island. Other sources of lambanog are coconut tuba and sugar cane, but the last named is considered an inferior source.

If allowed to ferment through the action of yeasts, tuba begins to sour by late afternoon. Kept in covered earthen jars, called tapayan, tuba becomes a vinegar known for its sourness and distinct flavor notes that cannot be found in vinegar from other sources like rice wine and sugar. Paombong, Bulacan is noted for its tuba vinegar, called eponymously, sukang Paombong.

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of duhat or lumboy

Duhat Syn. lumboy, longboy.

Another fruit that evokes childhood memories, duhat or lomboy. English is Java plum (Syzygium cumini L.).

Like the santol duhat is a summer fruit. The fruit comes in clusters, has a thin purple skin and white pulp. Like the santol there is hardly anything to eat, as it has a big seed relative to the size of the fruit. Duhat is eaten by being dipped in salt and sugar because the fruit is generally sour and tart. It is also shaken in a glass container with salt and sugar. The resulting mash is a child’s summer delight. The trees leathery leaves are rolled and dried as cigarette wrapping or as substitute for tobacco.

Worth noting: Kamel uses the Visayan word for duhat, which is longboy or lumboy rather than the Tagalog word. This suggests that he was acquainted with Visayan plants, which he probably knew from reports submitted by Jesuit missionaries in the Visayan islands of Samar, Leyte, Panay, Cebu and Bohol. He may have also visited these islands.

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of a male antipolo leaf

Antipolo also atipolo, tipolo (Artocarpus blancoi (Elm.) Merr.). Except for shade and occasional use for lumber, this member of the breadfruit family bears fruit, which is not eaten—usually. The tree is dimorphic, the male recognized by its parted leaf and the female by its obovate leaf.

But the tree is the stuff of legend and gave its name to hilltop town now a city in the ‘burbs of Manila. Antipolo is the site of the shrine to the Virgin Mary under the title of Nuestra Señora de la Paz y Buenviaje. The name refers to a small ebony statue of the Immaculate Conception given as a gift to the Jesuits by Gov. Gen Juan Niño de Tabora in 1626. The Jesuits took the gift to a mission station they were running and enshrined it in the mission church.

Not long afterwards, the image was chosen as the patron of the galleon, which plied the Manila-Acapulco trade route. The voyages, where this image was carried and where the passengers and crew evoked the intercession of the Virgin Mary, did the round trip successfully. No violent storms, no dangerous shoals, no pirates or armadas of Spain’s enemies for a total of 14 voyages.

In gratitude, the image was returned to its mountain shrine in a fluvial procession through the Pasig River. Beginning in Manila, the procession wove through Pasig’s meandering stream until it reached Laguna de Ba-e and the lakeshore town of Taytay, whence the procession proceeded on foot for the rest of the journey. This processional route would be traced annually by pilgrims who went to visit the shrine during the month of May. In colonial times, it was de rigueur to visit the shrine for anyone about to embark on a long journey. For being patroness of successful ocean voyages, the image earned the title Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage.

Oral tradition has it that the first Mass, and subsequently the first church of Antipolo, was at a site now called Pinagmisahan. But after the return of the image, the image would disappear from the altar time and again and after diligent search was found again and again on top of an antipolo or tipolo tree. This mysterious translation of the image, which generally happened at night, was read as a sign that the Virgin wanted a bigger church built on the spot where the image was found.

Heeding this divine missive, the townspeople built a sumptuous shrine at the new site in the 17th century. By 1715, the church was lavishly decorated, thanks to the donations of numerous patrons who believed that the image was miraculous.

The annual summer pilgrimage to Antipolo is vibrant as ever. But the old riverine processional route is no longer followed. Instead pilgrims go to Antipolo by car or by foot through two roads about 18 kilometers long, that lead up the hill. The volume of pilgrims has so increased that the official “pilgrimage month” begins in late March and extends to mid-July.

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of saint ignatius bean

Igasud [Strychnos ignatii Berg.] also known as katalonga, katbalonga, katbalongan, agwason, dankagi, gasud, kanlara. Faba Sancti Ignatii (Portuguese). Nux vomicae.

July is the month of St. Ignatius Loyola. This year is special because it is the 450th anniversary of his death; he died 31 July 1556. A medicinal plant was named after him known in the Visayas as igasud.

Before there was Prozac or Valium, there was igasud, listed in the ancient medicinal books as a remedy for emotional distress such as grief and anxiety, and the physical symptoms these cause like insomnia and bedwetting. It is also recommended in homeopathic medicine as a remedy for those afflicted with the “3 S’s … sitting, sighing, sobbing” sure sign of the broken hearted (drluc.com Homeopathic Remedies for the 21st century).

The Jesuits introduced the seed of this plant to Europe and gave it the name St. Ignatius bean. Franz Seidenschwarz describes the plant as “a large, woody vine with opposite leaves, white flowers and globose yellowish fruits.” The seed is used as a folk cure for stomach pain (Seidenschwarz, 1994. Plant world of the Philippines, p. 122). It is said that the plant was discovered in the Philippines whence it was disseminated throughout the medical world. The eminent Philippine historian Fr. Horacio dela Costa, S.J. suggests so; he writes: “Brother Kamel seems to have been the first to call the attention of European pharmacologists to the Saint Ignatius bean … one of the plants from which strychnine is derived. The ‘bean’ is really the seed of a vine known to the Visayans as igasud, and probably got its Spanish name from the Jesuits of Catbalogan, where it was common” (Dela Costa, 1961, Jesuits in the Philippines: 1581-1768 [Cambridge: Harvard University Press], p. 557).

However, Kamel’s notation that the term was from Portuguese (Lusitanis) suggests that the nut was discovered elsewhere. Spanish rather than the Portuguese Jesuits were assigned to the Philippines; if the Spanish Jesuits introduced the plant to the pharmacological world, why would Kamel ascribe the obviously Latin name to the Portuguese and not to the Spanish? Why then is the bean’s naming ascribed to the Portuguese?

It is possible that the bean may have indeed originated in the Philippines and was discovered by the Portuguese Jesuits through the lively Asian trade. They may have known the seed first before the plant. Prior to European colonization goods have been brought to and from the Philippines—to as far as the Middle East, thanks to the sailing prowess of Muslim traders from the Arabian peninsula. The loose ovate seeds of about 25 mm length, rather than the fruit, which contained about 10 to 15 tough seeds, were probably traded in the Asian market as medicine. Perhaps, the Jesuits were already familiar with the seed before they landed in the Philippines, where the botanist Kamel would learn about the plant from which this marvelous seed came. This would then be similar to the introduction of Jesuit bark or quinine to the European market. Powdered bark was first traded in the market and only subsequently did the tree from which it came became known to Europe. Jesuits are not even credited with introducing this medicine to Europe but they did have a lively trade in the bark, procuring it from their mission stations, so that they had a virtual monopoly of the trade, hence the name.

The active mood-changing ingredient, which makes the Ignatius bean still an important ingredient in homeopathic medicine is Strychnine, hence, the scientific name Strychnos Ignatii or iganita amara.

Now I wonder if the Jesuits of old used this wonder drug to arrive at consolation or whether they prescribed it to retreatants, who were in spiritual doldrums. Hard to know and hard to check this days because the bean has been eased out of the market by more efficient ways of extracting strychnine from other sources.

Monday, July 03, 2006

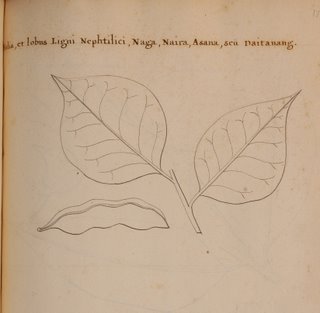

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of narra

Narra [Pterocarpus indicus Wild] Syn: nara, naga, dungos, asana. This is a large tree growing to 25 m. If left to grow apart from other trees it develops a wide crown, but in dense tropical forests it grows straight and tall and has a crown at the very top. The trunk is supported by buttress roots called dalig in Tagalog. The tree is indigenous to Southeast Asia. It sheds its leaves after the cold season and quickly shoots young leaves better adapted to the coming summer months. Around March or April, narra blooms profusely but for a short time. After one day its small bright yellow flowers fall to the ground. After that seed pods develop.

Narra also known as Philippine mahogany is treasured for its fine-grained reddish brown or blond hardwood (narrang-pula and narrang-puti or narra blanca, respectively). Tindalo or balayong (Afzelia rhomboides Vidal) is often mistaken for red narra, which it resembles. Tindalo as the scientific name points out belongs to an altogether different genus from narra. The confusion is further exacerbated because tindalo is also known as mahogany. The term “mahogany” does not designate a particular tree; mahogany rather is a trade name for lumber that may come from various hardwood trees like narra or balayong or yakal (Shorea astylosa) or the South American mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) introduced as landscaping material by the Americans early in the 20th century. Mahogany’s characteristics are that it close-grained, tropical in origin and has a reddish brown hue.

Polished to a shine narra is used for furniture, floor and wall boards. The lumber tends to retain its natural oil for years and hence is easy to maintain. It is hardly used as structural members of a house that being answered by harder woods like molave, dungon and the like.

The narra is the Philippine national tree.

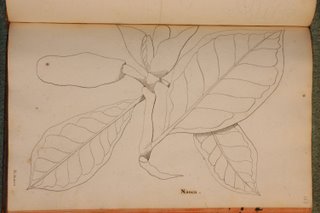

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of molave

Molave [Vitex parviflora] Syn: mulawin, mulawun, tugas

This resilient tree can compete with kamagong for hardness. The appeal of its lumber, however, is its light blond color. This hardy tree grows even in rocky soil. Its tough roots can slowly crack stone as the tree seeks for nourishing water. Molave grows to 15 meters. It sends out small blue flowers before or during the summer months, which mature into globose berries up to 6 cm in diameter.

Molave lumber is used for posts, floor boards, furniture and for contrasting wood inlay. For furniture, molave is not highly recommended because the lumber is “malikot”, that is, it shrinks and expands with changes in weather. It is also hard to work because, carpenter’s say, its grains are not straight but curve like rivulets.

“Like the Molave” is well-known literary piece by Rafael Zulueta da Costa. It won the Commonwealth Literary Award for Poetry. Ironically, it was an anti-American piece, and how it passed the judges is a big question. It challenges the Filipino to grow like the molave.

The poem begins by calling national hero José Rizal to rise once more and lead his people grown weak and dependent on a new set of colonial masters and ends with the stirring conclusion:

I want our people to grow and be

like the molave, strong and resilient,

rising on the hillside, unafraid,

of the raging flood, the lightning or

the storm, confident of its own strength.

Lines attributed to Manuel L. Quezon, the president of the Commonwealth.

Friday, June 30, 2006

ateneo and zero-in

The exhibit "Flora: beauty, desire and death" is scheduled to open at the Ateneo Art Gallery in October. "Flora" is Ateneo's participation in Zero-in, a yearly effort by four institutions—the Ateneo Art Gallery, the Lopez Museum, the Museong Pambata (Children's Museum) and the Ayala Museum, now housed in a new and bigger building. The Zero-in exhibition is the major show for the year of the participating institutions.

Ateneo is currently exhibiting the works of Ronald Ventura, who won last year's Ateneo Art Awards. The Ventura show will run till late July. On 8 August 2006, the winners of the Ateneo Art Awards for 2006 will be announced at the Rockwell Center. A show of the finalist for the award will be held at Rockwell after which the show will transfer to the Ateneo Art Gallery. For details log in at the Ateneo Art Gallery site at gallery.ateneo.edu or click the link on this page.

Ateneo is currently exhibiting the works of Ronald Ventura, who won last year's Ateneo Art Awards. The Ventura show will run till late July. On 8 August 2006, the winners of the Ateneo Art Awards for 2006 will be announced at the Rockwell Center. A show of the finalist for the award will be held at Rockwell after which the show will transfer to the Ateneo Art Gallery. For details log in at the Ateneo Art Gallery site at gallery.ateneo.edu or click the link on this page.

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of nangka or jackfruit

Nangka [Artocarpus heterophyllus Lamk. Syn: A. integra (Thunb.) Merr.] Syn: Nanca, langka belongs to the breadfruit genus of the Moraceæ family. Its close relations are camansi (A. altilis (Parkins) Fosb), antipolo or tipolo (A. blancoi (Elm.) Merr.), kubi (A. nitidus) and marang (A. odoratissimus). It is known in English as jackfruit.

Nangka grows to 15 m, has a milky sap and produces female and male heads. Fruits generally develop in new growth around the trunk as the fully mature fruit can be as large as 60 cm. The composite fruit matures from green turning yellow when ripe. Inside the ripe nangka, pockets of golden yellow flesh surround numerous seeds. This is eaten as is, after removing the seed. The golden flesh is used for dessert, for which it can be preserved by boiling in syrup. This sweetened nangka is an ingredient in halo-halo. Nangka is also cooked with saba or frying banana when making turon. Nangka ice cream is a unique product of the Philippines.

Green nangka is treated as a vegetable and cooked with coconut milk flavored with a bit of meat or shrimp. The seeds can be boiled or roasted and eaten like a nut.

Nangka wood, when dried and properly treated is used for manufacturing guitars in Cebu. Elsewhere in Asia, the wood is used for stringed and percussion instruments.

Thursday, June 29, 2006

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of santol

Santol [Sandoricum koetjape] Syn. hantol

Santol is associated with childhood memories. There are two popular varieties: the native and the Bangkok, known for its large fleshy fruit and introduced to the Philippines in the 1950s. Blooming during the cold months, the fruit matures as summer approaches. By late March or April, when classes are on summer break, santol satisfies the hunger for something sweet and slightly tart. Its yellow fruit encloses a clutch of five seeds covered with white stringy pulp that is sucked rather than eaten. The adventurous youngster swallows the seed as big as an adult’s thumb, headless of the warning that the ingested seed will germinate inside the stomach and in time force its way out of the nostrils, ears and other orifices of the body. This, of course, is urban or rather rural legend but there is always a sweet thrill daring to do the dangerous.

Santol can be eaten au naturelle, split the fruit and suck out the seeds and pulp. Add a bit of salt, if you please. Or it can be peeled so that more of the soft rind is kept, and the fruit is salted if you so please. A bit more complicated is storing the peeled santol in a jar and covering it with brine laced with sugar. Also easy to make is santol juice. Santol pealed and quartered is placed in a glass pitcher to which is added honey and water to cover. The mixture is then chilled for about three hours as the santol’s flavor leaches to the water. The santol flesh turns brownish because of oxidation the resulting juice has a light amber color like apple cider.

Tuesday, June 27, 2006

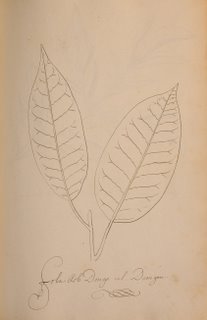

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of dungon leaf

Dungon [Heritiera littoralis Dryand. Ex W. Ait] Syn. Dongo

This slow-growing hardwood three was used extensively as posts for the colonial house or bahay na bato because the lumber was impervious to moisture and resistant to even the most assiduous termite. Even if the dugon or dungon-late, is a small tree, growing to about 10 meters, it was also used as post for the lofty church nave, in which case trunks of dungon were joined together.

Dungon thrives best along the seashore or in coastal forests. Its seed has a very tough shell and needs to be soaked in water for a while before it germinates. Dungon has yellowish-green bell-shaped flowers.

It is also known as dungon-mangle, dungon-lawlaw, dungon latian, maladungon and malarungon.

josef george kamel, s.j., pandakaki

Pandakaki Syn. Pandakaki-tipod, pandakaki puti (Tabernaemontana pandacaqui) belongs to the Apocynaceæ family, which includes such diverse looking plants as common oleander or adelfa, Plumeria rubra forma rubra or calachuchi, and the genus Allamanda of which the best-known species is the large yellow bell. Pandakaki is a shrub that grows up to 3 meters tall. It has white flowers and dark seeds, and like many of the Apocynaceæ family its sap is milky white and sticky. Endemic to the Philippines, pandakaki grows wild on limestone hills and is rarely cultivated as an ornamental.

Monday, June 26, 2006

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of chico fruit and leaf

Chico (Manilkara zapota (L.) Van Royen) is a tree introduced to the Philippines from Mexico during the Spanish period. It is known as sapodilla in Spanish. This small tree, up to 5 meters, is grown in orchards and in home gardens. It is multi-branched, has shiny, leathery green leaves and bears a fleshy, brown fruit. When ripe it is sweet. The fruit has a gritty texture and is eaten as is or mixed with salad for its texture. Chico fruits profusely during the hot season and is one of summer’s delights for its refreshing quality, especially if served chilled.

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of katuray

Katuray (Sesbania grandiflora (L) Pers. Called gaway-gaway in Visayan, the katuray tree can grow to 10 meters. The leaf is compound consisting of numerous green leaflets. The katuray flowers are either white or red. Both flower varieties are edible and have been part of traditional cuisine. Nouvelle cuisine Philippine has discovered uses for katuray by incorporating it with salad greens for added color and taste.

Sunday, June 25, 2006

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of camansi or breadfruit

Kamansi Syn. camangsi or camansi [Artocarpus altilis (Park.) Forsberg Syn. A. communis J.R.&G. Forst., A. incisa (Thunb.) L. f., A. camansi Blanco].

Belonging to the breadfruit family of which the better-known relation is the nangka or langka, camansi has two varieties: the seed-bearing kamansi and the non seed-bearing kolo. Kolo is considered as the “true breadfruit.”

Kamansi, mistakenly called rimas in Tagalog (rimas is a different species), figures in Visayan cuisine where the unripe camansi is cut up as a vegetable and cooked with pork hock. The seeds are roasted and served as a snack.

Saturday, June 24, 2006

what i learned from the net

Interest in the contribution of Bro. Josef Georg Kamel, S.J. has spurred an exhibition in Bruno, featured in the Maxims and Minims of The Company Magazine, published by the Jesuit American Assistancy. The online version's address is http://www.companymagazine.org/v233/minimsandmaxims.pdf.

Jesuitica, the online site of The Maurits Sabbe Library at the Catholic University Leuven has a section entitled question and answer where these remarks of Luc Dhaeze, who describes himself "as an amateur botanist" who has been "growing camellias for years" about the camellia and the provenance of the Kamel illustrations in Louvain are posted:

1. On the camellia. "Most literature so far has assumed Kamel never saw the camellia. This looks highly improbable. After all, he made a drawing of the plant, as is seen in this manuscript housed in Leuven. Most probably the Chinese or Japanese took this plant to the Philippines. Although he did not discover the plant, I'd venture to state that he knew the plant. A statement backed by Prof. Dr. Klaus Peper in his on-line article Georg Joseph Kamel: Apothecarius, medicus, botanicus (1997). Unfortunately enough I have no access to the texts of John Ray that go with the drawings of Kamel. They might have shed some additional light.

According to Sommervogel (Bibliothèque de la Compagnie de Jésus, book 2, col. 580) John Ray (British clergyman and botanist, 1625-1705) used the data from Kamel, but never published the drawings. A leaflet, pasted into the manuscript, by Ant. Laurent de Jussieu contains the concordances with the corresponding European names of the plants."

2. On the illustrations. "Whether the drawings of the Leuven manuscript are originals or copies has been a question of much discussion during the past century, as is testified to in the correspondence kept with the manuscript. As of now, three drawings (83, 175 and 185) are deemed to be original, whilst the others are copies.

The manuscript came into the possession of French botanist Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (1748-1836), and was bought by the Belgian count Alfred de Limminghe (Gentinnes) on February 6, 1858 at the sale of the possessions of the former. De Limminghe presented the manuscript as a gift to the Jesuit college in Leuven."

Luc Dhaeze, Belgium lucdhaeze@skynet.be

It's a bit of a disappointment if the rest of the more than 200 illustrations did not come from Kamel's hand, but if they are faithful copies, and there seems to be no reason to suppose they are not, then the drawings represent what Kamel has brought to the attention of European savants. Copying of illustrations and manuscripts was common practice in a day and age when the handwritten text was still the principal means of preserving and transmitting data. Such copying was done to texts and illustrations sent from Manila to Spain or Rome. The five-volume manuscript of Francisco Alzina, Historia de las Islas e Indios de Bisayas, exist only as a copy. Even the older San Cugat text from which the Palacio Real recension is copied—text and illustration—is deemed a copy. Yet, the Alzina is considered an important source text for information about the geography and topography, flora and fauna, inhabitants and history of the Visayas, especially the islands of Samar and Leyte.