what i learned from the net

Interest in the contribution of Bro. Josef Georg Kamel, S.J. has spurred an exhibition in Bruno, featured in the Maxims and Minims of The Company Magazine, published by the Jesuit American Assistancy. The online version's address is http://www.companymagazine.org/v233/minimsandmaxims.pdf.

Jesuitica, the online site of The Maurits Sabbe Library at the Catholic University Leuven has a section entitled question and answer where these remarks of Luc Dhaeze, who describes himself "as an amateur botanist" who has been "growing camellias for years" about the camellia and the provenance of the Kamel illustrations in Louvain are posted:

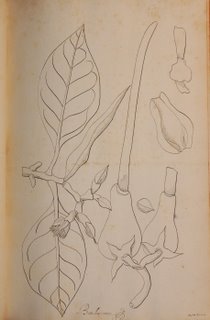

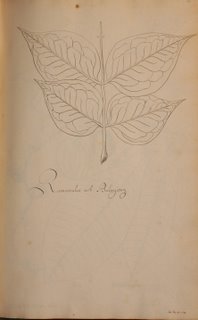

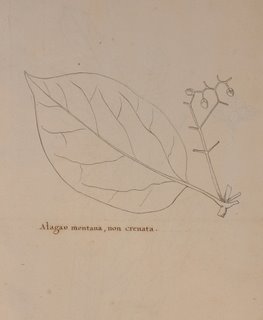

1. On the camellia. "Most literature so far has assumed Kamel never saw the camellia. This looks highly improbable. After all, he made a drawing of the plant, as is seen in this manuscript housed in Leuven. Most probably the Chinese or Japanese took this plant to the Philippines. Although he did not discover the plant, I'd venture to state that he knew the plant. A statement backed by Prof. Dr. Klaus Peper in his on-line article Georg Joseph Kamel: Apothecarius, medicus, botanicus (1997). Unfortunately enough I have no access to the texts of John Ray that go with the drawings of Kamel. They might have shed some additional light.

According to Sommervogel (Bibliothèque de la Compagnie de Jésus, book 2, col. 580) John Ray (British clergyman and botanist, 1625-1705) used the data from Kamel, but never published the drawings. A leaflet, pasted into the manuscript, by Ant. Laurent de Jussieu contains the concordances with the corresponding European names of the plants."

2. On the illustrations. "Whether the drawings of the Leuven manuscript are originals or copies has been a question of much discussion during the past century, as is testified to in the correspondence kept with the manuscript. As of now, three drawings (83, 175 and 185) are deemed to be original, whilst the others are copies.

The manuscript came into the possession of French botanist Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (1748-1836), and was bought by the Belgian count Alfred de Limminghe (Gentinnes) on February 6, 1858 at the sale of the possessions of the former. De Limminghe presented the manuscript as a gift to the Jesuit college in Leuven."

Luc Dhaeze, Belgium lucdhaeze@skynet.be

It's a bit of a disappointment if the rest of the more than 200 illustrations did not come from Kamel's hand, but if they are faithful copies, and there seems to be no reason to suppose they are not, then the drawings represent what Kamel has brought to the attention of European savants. Copying of illustrations and manuscripts was common practice in a day and age when the handwritten text was still the principal means of preserving and transmitting data. Such copying was done to texts and illustrations sent from Manila to Spain or Rome. The five-volume manuscript of Francisco Alzina, Historia de las Islas e Indios de Bisayas, exist only as a copy. Even the older San Cugat text from which the Palacio Real recension is copied—text and illustration—is deemed a copy. Yet, the Alzina is considered an important source text for information about the geography and topography, flora and fauna, inhabitants and history of the Visayas, especially the islands of Samar and Leyte.

My interest in Kamel is not just scholarly. Although I am not a trained botanist, I enjoy gardening and for the past two years have been helping landscape and improve the gardens at the retreat house, Mirador Jesuit Villa, in Baguio City. The house is about to celebrate its centennial, having been established in May 1907. To my disappointment, I did not find too many camellia cultivars in the nurseries in Baguio as I wanted to build a camellia garden to honor Kamel. The single-petal Thea sinensis was also not available. The cool mountains of Baguio is the only place where camellias thrive, in the warm lowlands it has a hard time flourishing.

Jesuitica, the online site of The Maurits Sabbe Library at the Catholic University Leuven has a section entitled question and answer where these remarks of Luc Dhaeze, who describes himself "as an amateur botanist" who has been "growing camellias for years" about the camellia and the provenance of the Kamel illustrations in Louvain are posted:

1. On the camellia. "Most literature so far has assumed Kamel never saw the camellia. This looks highly improbable. After all, he made a drawing of the plant, as is seen in this manuscript housed in Leuven. Most probably the Chinese or Japanese took this plant to the Philippines. Although he did not discover the plant, I'd venture to state that he knew the plant. A statement backed by Prof. Dr. Klaus Peper in his on-line article Georg Joseph Kamel: Apothecarius, medicus, botanicus (1997). Unfortunately enough I have no access to the texts of John Ray that go with the drawings of Kamel. They might have shed some additional light.

According to Sommervogel (Bibliothèque de la Compagnie de Jésus, book 2, col. 580) John Ray (British clergyman and botanist, 1625-1705) used the data from Kamel, but never published the drawings. A leaflet, pasted into the manuscript, by Ant. Laurent de Jussieu contains the concordances with the corresponding European names of the plants."

2. On the illustrations. "Whether the drawings of the Leuven manuscript are originals or copies has been a question of much discussion during the past century, as is testified to in the correspondence kept with the manuscript. As of now, three drawings (83, 175 and 185) are deemed to be original, whilst the others are copies.

The manuscript came into the possession of French botanist Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (1748-1836), and was bought by the Belgian count Alfred de Limminghe (Gentinnes) on February 6, 1858 at the sale of the possessions of the former. De Limminghe presented the manuscript as a gift to the Jesuit college in Leuven."

Luc Dhaeze, Belgium lucdhaeze@skynet.be

It's a bit of a disappointment if the rest of the more than 200 illustrations did not come from Kamel's hand, but if they are faithful copies, and there seems to be no reason to suppose they are not, then the drawings represent what Kamel has brought to the attention of European savants. Copying of illustrations and manuscripts was common practice in a day and age when the handwritten text was still the principal means of preserving and transmitting data. Such copying was done to texts and illustrations sent from Manila to Spain or Rome. The five-volume manuscript of Francisco Alzina, Historia de las Islas e Indios de Bisayas, exist only as a copy. Even the older San Cugat text from which the Palacio Real recension is copied—text and illustration—is deemed a copy. Yet, the Alzina is considered an important source text for information about the geography and topography, flora and fauna, inhabitants and history of the Visayas, especially the islands of Samar and Leyte.

My interest in Kamel is not just scholarly. Although I am not a trained botanist, I enjoy gardening and for the past two years have been helping landscape and improve the gardens at the retreat house, Mirador Jesuit Villa, in Baguio City. The house is about to celebrate its centennial, having been established in May 1907. To my disappointment, I did not find too many camellia cultivars in the nurseries in Baguio as I wanted to build a camellia garden to honor Kamel. The single-petal Thea sinensis was also not available. The cool mountains of Baguio is the only place where camellias thrive, in the warm lowlands it has a hard time flourishing.