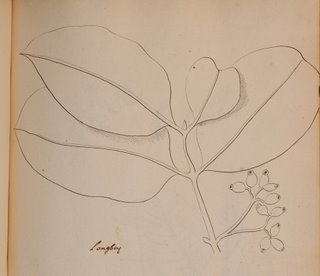

josef george kamel, s.j. drawing of nipa

Nipa [Nipa fruticans or Nypa fruticans]

“Bahay kubo, kahit munti.” The cube-shaped ubiquitous bahay or balay was a staple of countryside scenery. Today, the balay is disappearing replaced by reinforced concrete, glass and galvanized iron sheet houses in pseudo-Mediterranean or neo-Spanish colonial style, the fruit of hard-earned cash by overseas Filipino workers. But these results of “katas ng Saudi” or Japan, Kuwait, or wherever Filipinos are (and that’s everywhere on the planet) has not erased the mythic aura of the simple and small one-room bahay. It is still part of the national imaginary, resurrected whenever there is need to look Filipino and rural.

This bahay, this dwelling, is truly the fruit of the land, as it is built completely of vegetable matter: bamboo, vines, coconut trunks, timber and—nipa. (Of course, there are those to take short cuts by replacing bamboo dowels with nails, but that’s not how the traditional bahay was built).

Nipa or sasa is known as attap palm, mangrove palm or nipah in the Malaysian Peninsula. Attap in Melayu simply means roof. Nipa grows near the shore often in association with mangrove. Its habitat are the tidal swamps surrounding islands and the banks of waterways leading to the sea. Nipa grows best where tidal and river currents are slow and where there is a generous layer of soft black nutrient rich mud. Part of the plant is submarine, as its roots and short trunk are submerged under water. What rises above the water are the leaves and the flower stalks.

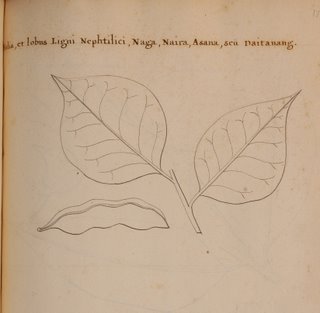

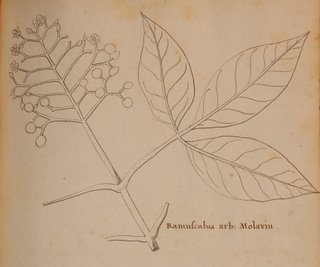

Kamel presents a set of drawings of the nipa, capturing quite accurately the globular inflorescence of the female flowers and the catkin-like male flowers below.

The leaves can grow as high as 9 meters and the flowers mature into a globular cluster of seeds about 25 cm across. As seeds ripen they fall one by one and are dispersed by the tide.

Architectural use: The compound leaf of the nipa produces broad but elongated leaflets. These are separated then folded over a bamboo stick and sewn together with rattan, vine or the outer sheath of the bamboo, drawn thin and fine like a cord. These shingles about a meter in length (width depends on the nipa leaf used) are laid on top of each other for roofing. The distance between shingles depends how thick (therefore how waterproof and long-lasting) the roof is meant to be. Closely shingled roofs with each shingle about an inch apart can last a decade, unless damaged by a strong typhoon or by fire.

In Capiz province, a folk unit used for measuring distances of shingles is the matchbox (approximately 1.25 in x 2.00 in). Closely shingled roofs are distant for the space of isa ka posporo nga nagahigda, that is, a matchbox laid horizontally, while the more distant measure is posporo nga nagatindog, that is, a matchbox laid vertically.

Culinary note: The nipa inflorescence like the coconut’s is tapped before blossoming and yields a sweet sap that is fermented to make tuba sa nipa, an alcoholic drink. In Quezon province, the tuba is processed by distillation to make the potent lambanog (pure alcohol 80 to 90 proof). This is lambanog sa sasa, commonly found in Infanta and Polilio Island. Other sources of lambanog are coconut tuba and sugar cane, but the last named is considered an inferior source.

If allowed to ferment through the action of yeasts, tuba begins to sour by late afternoon. Kept in covered earthen jars, called tapayan, tuba becomes a vinegar known for its sourness and distinct flavor notes that cannot be found in vinegar from other sources like rice wine and sugar. Paombong, Bulacan is noted for its tuba vinegar, called eponymously, sukang Paombong.